A private viewing of Robert Permeti’s painting The Abyss, which depicts Enver Hoxha’s confrontation with Brigadier ‘Trotsky’ Davies in January 1944

Playing ominously with a pearl-handed penknife and now suddenly ‘stern’, with a ‘taste of iron’ in his voice, Stalin proposed: ‘The artist ought to show life truthfully. And if he shows our life truthfully he cannot fail to show it moving to socialism. This is, and will be, Socialist Realism.’ In other words, the writers had to describe what life should be, a panegyric to the Utopian future, not what life was…

‘You produce the goods that we need,’ said Stalin. ‘Even more than machines, tanks, aeroplanes, we need human souls…’

… The writers, Stalin declared, were ‘engineers of human souls…’

From Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar, by Simon Sebag Montefiore

Not just writers. Communist regimes the world over were obsessed with the visual arts, not least Enver Hoxha’s Albania. Tirana’s small National Gallery has an intriguing collection of Socialist Realist works, and is definitely a must-visit if you’re in the city for a day or two. It drives home how important the events of World War II, and the fight against ‘fascism’ (a term used to describe domestic opponents as much as the Italians and German occupiers), were to the regime in terms of a founding myth.

There are two problems (in my view) with the gallery, though. First, there’s not enough background information on the artists and their works. Second, the picture that sits at the top of this blog, The Abyss, by Robert Permeti, isn’t part of the collection.

Last month, when Alex Smyth, whose father Captain Frank Smyth parachuted into Albania as part of Brigadier ‘Trotsky’ Davies’ Special Operations Executive mission, visited Albania, I was keen for him to meet Robert Permeti and ideally see The Abyss in the flesh (or oil and canvas, rather). I met Robert for a coffee with Elton Caushi of Albanian Trip a few weeks before Alex and his son Tom arrived, and we were delighted to discover that he (like me) was fascinated with the British involvement with Enver Hoxha’s partisans during 1943/44. We were also delighted to find that the painting hadn’t been sold abroad, despite some tempting offers, and was still in Tirana.

Alex Smyth listens to artist Robert Permeti at a private viewing of Permeti’s painting The Abyss, while Elton Caushi of Albanian Trip (centre) translates

Robert very kindly invited the Smyths to a private viewing of The Abyss, and talked about the history of the painting, and the effort he put in to accurately capturing the smallest details. The time we spent with him drove home how precarious was the position of an artist under totalitarian regimes.

‘The first title was The Abyss [this could also be rendered as “Precipice” in English], as I felt I was standing on the edge of an abyss,’ Robert told us.

When he began work on the painting in the late 1970s, he was an army officer from a devoted Communist family, and a True Believer.

‘Both my parents were partisans [during WWII],’ he told us. ‘When I started the painting I loved Enver. I was chief of my division’s propaganda section. But I had a brother who was a pilot, and he was punished under the propaganda law.’

With the trial of his brother, doubt began to creep into Robert’s mind. ‘I loved doing the research, but at that time there was a lot of debate [about Albania’s wartime ‘national liberation struggle’].’

A young Robert Permeti in Army uniform, during his research for The Abyss

Robert’s research was, with some understatement, thorough. ‘Socialist Realism is very rigorous in its rules,’ he told the Smyths. ‘Every detail needs to be thought out. The gun Enver holds was one the British gave him.’

Robert visited the villages that had sheltered Davies and Hoxha, searched the (heavily doctored, naturally) Albanian state archives, sketched landscapes, spoke to locals. And he also spoke to one man who had been with the British throughout…

‘What made my work harder was that during this time Enver published The Anglo-American Threat to Albania. Because of this I started to talk to Fred Nosi [the interpreter for Brig Davies’ mission]. Fred told me completely different stories to Enver’s.’

The Abyss captures the moment that Davies and Hoxha, after several days’ march through the mountains as they attempted to break through German encirclement, rowed over Davies’ plan to leave Hoxha and walk south to Korça with Fred Nosi.

‘… I shall go to Korça without you,’

‘You may want to do so, but I shall not allow it,’ I said.

‘Why, am I your prisoner?’ exclaimed the General, raising his voice.

‘No, you are not our prisoner but you are our ally and friend and I cannot allow the Germans to kill you… I am certain that you are going to your death or captivity, therefore I cannot allow you to take Frederick [Nosi] or any other partisan…’

From The Anglo-American Threat to Albania by Enver Hoxha

Hoxha claims that Davies advised him to surrender to the Germans, and that his (Hoxha’s) patience was exhausted and he reacted furiously, calling Davies a defeatist. A highly implausible scenario, knowing how bloody-minded and dedicated to his duty Davies was. And it seems that Fred Nosi, who was interpreting, had a different recollection from Hoxha’s.

‘Fred told me that in reality Hoxha acted like a gangster…’ Robert told us.

Brigadier ‘Trotsky’ Davies and his bodyguard Corporal Jim Smith in a detail from Robert Permeti’s The Abyss

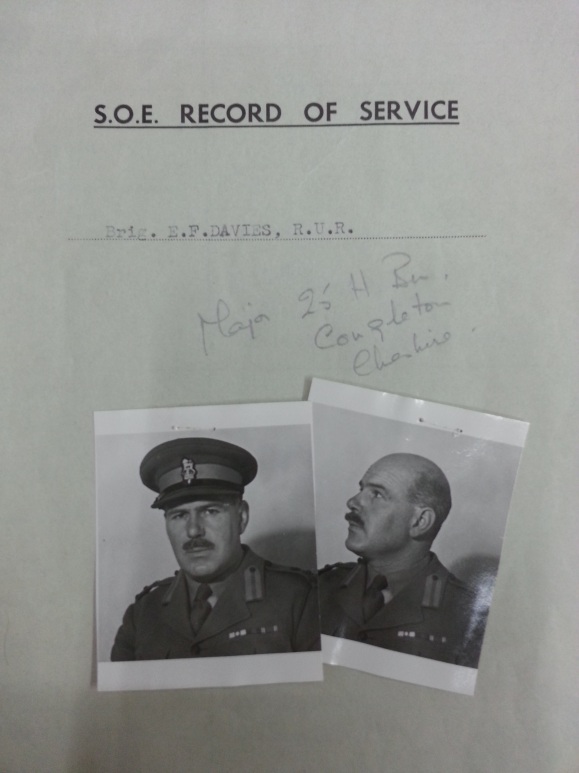

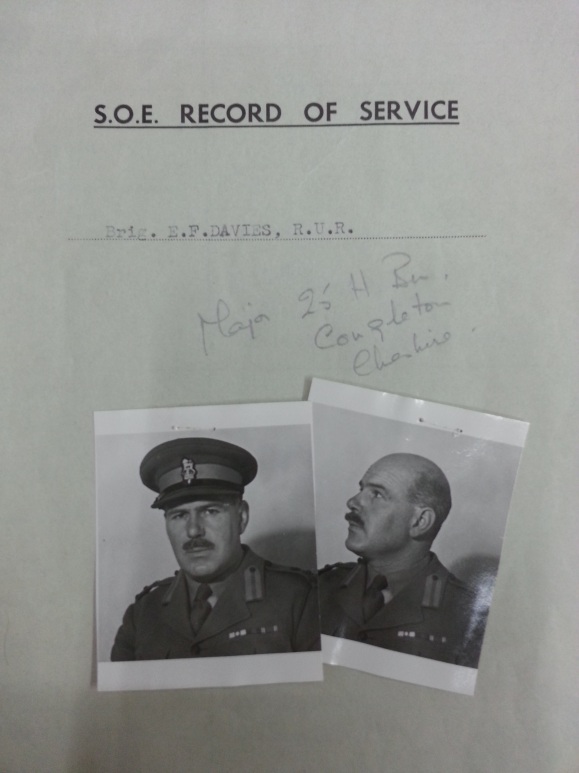

A key point of interest is the portrayal of Davies himself. The regime gave Robert a photograph taken of Davies, in British battle dress, during his stint in Albania, which you can see below.

The photograph given to Robert Permeti when he was researching The Abyss, purportedly of Brigadier Davies but a better match for an ancient Winston Churchill

The only problem is, whoever that is in the photo, it isn’t Davies. In fact it looks more like an aged Churchill. The picture does, however, beautifully back up Hoxha’s memorable portrayal of Davies as an ageing Colonel Blimp figure – a blustering British imperialist straight from Central Casting.

Davies was a middle-aged man, a bit portly, with a round face and a bulbous red nose (apparently he liked his whisky)… The most hard-worked word of his vocabulary was ‘I’… He was carrying a stick, a real walking stick and not one of those fancy batons British officers like to carry. As to his age, he must have been well on in his fifties [actually Davies was 42]…

From The Anglo-American Threat to Albania by Enver Hoxha

The real Brigadier ‘Trotsky’ Davies’ pictured in his SOE personal file (National Archives HS9/399/7)

Notice too the ‘RAF’ emblem on Davies’ beret. In TAATTA, Hoxha writes of Davies wearing RAF insignia but then refusing to admit that he was an Air Force intelligence officer. An agent of Perfidious Albion failing to pull the wool over the ever-vigilant Enver’s eyes. Actually simple confusion on Hoxha’s part – Davies, who was a regular officer in the Royal Ulster Rifles, wore parachute wings, as did all SOE officers who dropped into Albania. Wearing the wings indicated you had parachuted in action, not just in training. For the younger officers wearing these wings more or less meant guaranteed sex with impressionable FANYs (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry) in Cairo, where SOE’s Balkan missions were run from till early 1944. Well worth wearing, then.

The second Briton in the picture is Corporal Jim Smith. He, it’s worth mentioning, had at the Battle of Peza in October dragged the already dead body of Bombadier William Hill to cover from under German machine-gun fire, and would refuse to abandon Davies when he [Davies] was shot through the liver and captured by the Germans a few days after the scene depicted in the painting.

Robert finished work on The Abyss in time for a major art exhibition, in 1981. Then a problem arose. Enver’s influential wife, Nexhmije, liked the painting, but wanted one small change to be made – for Robert to remove the British. He refused.

‘I was completely under the influence of Fred Nosi,’ Robert says. ‘I entered into a difficult psychological state. I didn’t think before giving the work the title The Abyss. Only later did I understand how dangerous this was for me. I realised it was two different worlds facing each other. The gap between the two worlds was filled with Eastern influence.

‘If you look at the painting you can see that Enver looks emotionally tired. Davies, though old, looks energetic.

Robert Permeti poses with his painting The Abyss, after the fall of the Communist regime

‘I was taking a risk. I could have gone to prison. But the advantage I had was the painting had huge impact. The foreign diplomats [who attended the show’s opening night] wold stop and stare. The diplomats from pro-Hoxha countries would look from a distance. This painting allowed me to be more daring in my later work.’

The risk Robert took was real. Going to prison was not an uncommon punishment for artists who stepped out of line with the Communist regime. Later, when he took us around the National Gallery, he pointed out works whose creators had endured jail terms for some perceived ideological failing.

‘No artist was imprisoned for stealing or killing anyone,’ he told us. ‘These were the intellectual people. They didn’t deserve to go to jail.’

The Smyths’ meeting and gallery tour with Robert Permeti was arranged as part of their 11-day Drive Albania tour. If you’re visiting Tirana and would be interested in a tour of the National Gallery with a Socialist Realist artist, contact Elton at Albanian Trip.